User Tools

Click for Menu of Articles

Table of Contents

This paper was covered at a journal club called Deep Dive, part of Biotech without Borders.

A Prospective Analysis of Genetic Variants Associated with Human Lifespan

20190901

Kevin M. Wright, Kristin A. Rand, Amir Kermany, Keith Noto, Don Curtis, Daniel Garrigan, Dmitri Slinkov, Ilya Dorfman, Julie M. Granka, Jake Byrnes, Natalie Myres, Catherine A. Ball and J. Graham Ruby

https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.119.400448

Abstract

A GWA (genome wide association) study was conducted using the AncestryDNA and UK Biobank. Previous studies had been done before on the individual data sets. This study increased the statistical power by increasing the total number of subjects.

The challenge of correlating lifespan with genetics, is that “genotypes are generally gathered from living persons, whereas lifespan (total elapsed time between birth and death) is a property of deceased persons. Due to this challenge, current age has been used as a lifespan proxy trait in many human aging studies.” However, as decades go by and additional studies are done using age as a lifespan proxy, there will be confounding factors having to do with such things as the advancement of medicine or increases in pollution.

While the genomes of children are related to those of the parents, the loci related to lifespan will be shared fractionally, and the fractions may vary based on the loci. Thus, a very large sample size is required for statistically significant conclusions. Several previous parental-lifespan studies have been conducted using the UK Biobank. To improve on the sample size, the data from AncestryDNA was combined with that from the UK Biobank.

While it is difficult to measure the genetic contribution to variation in human lifespan, the estimation is that the heritability effect of lifespan is under 10 percent. One confounding factor is social inheritance, where people are born into social factors that can contribute to better health or lifespan. Another confounding factor is assortative mating, a form of sexual selection where individuals that have similar appearance tend to mate with each other more frequently than if the mating was random (birds of a feather flock together).

Different races have different life expectancies, not only because of genetics, but also the socioeconomic factors they are born into. Isolating and quantifying the contributions to lifespan from these types of confounding variables is not possible with current methods.

Phenotypes such as lifespan are influenced by more than one gene. Looking individually at each gene that affects lifespan, there are gene variants. Some of these variants result in the same phenotype, while some can cause differences in lifespan. The ones that do not cause differences are often grouped together, or classified as the same gene type, or allele.

Variants where a single nucleotide in the DNA is altered often result in the same allele. These single nucleotide differences are referred to as SNP (single nucleotide polymorphism) variants. SNP's can arise in any of the cells of the body due to mutations. While mutations are infrequent, they occur because the DNA copying process is imperfect.

As a population grows older, members of the same age with alleles that reduce lifespan, will die off first. The cells within an individual also mutate, but at a very slow rate. So slow, that DNA samples from the same person, taken 80 years apart, would still show a majority of cells having the original DNA. However, there are cases of clonal mosaicism, where a mutation can give rise to body regions with a different genome.

There may be some cases, however, where mutations have a survival advantage compared to neighboring cells, and are able to gain majority. An example of this is cancer. However, it is unlikely that DNA samples will be composed of a majority of mutated cells.

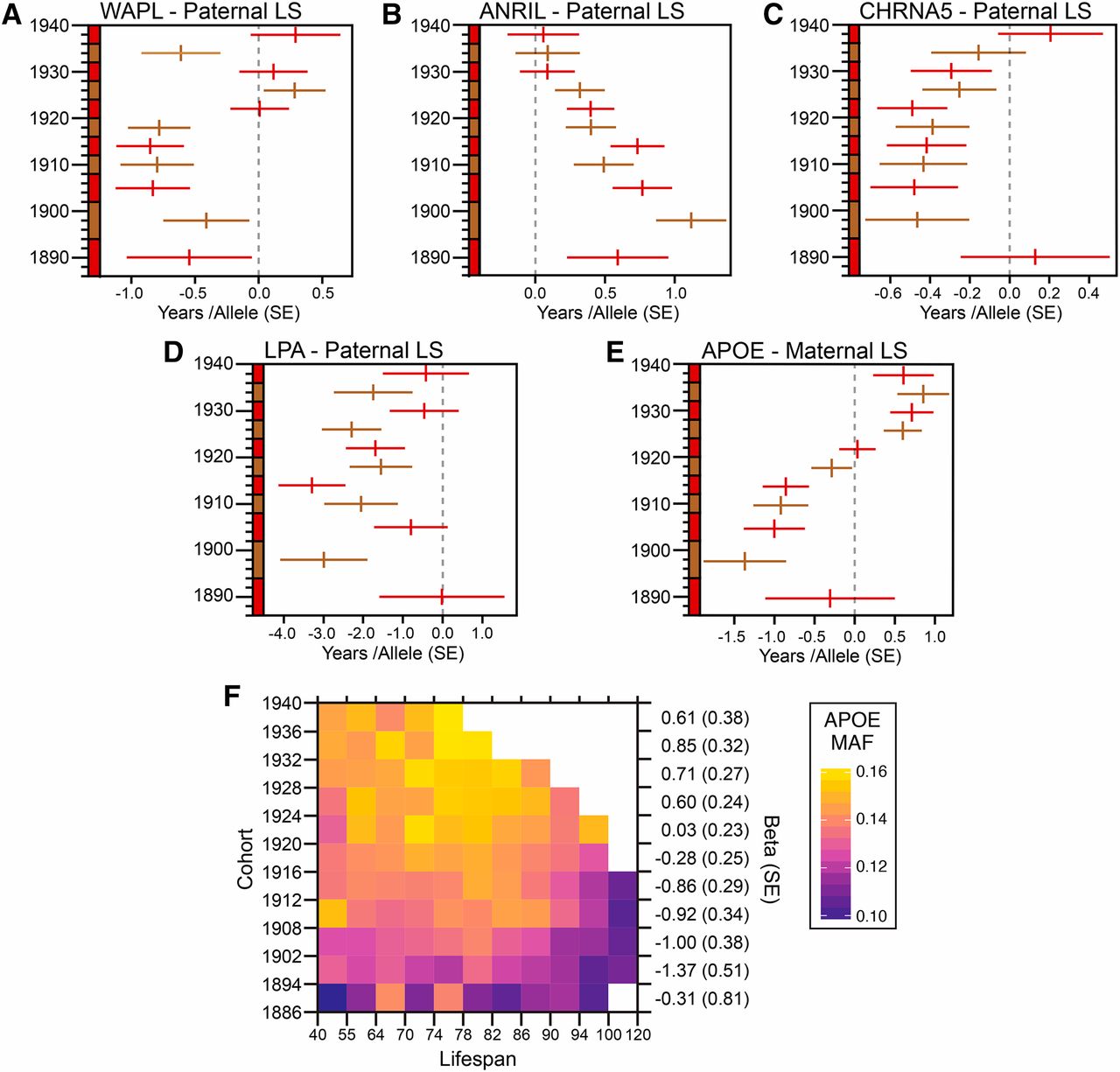

Of interest is that loci associated with maternal lifespan do not correspond with paternal lifespan. “In total, this meta-analysis identified eleven paternal and four maternal lifespan-associated loci, two of which have not previously been associated with parental lifespan.”

Materials and Methods

Customer generated pedigrees are stitched together and unified, creating a duplicate-free ancestry. Recorded lifespans between 40 and 120 years were used, to reduce noise from deaths unrelated to old age. Approximately 1/3 of individuals before 1900 are missing a death date.

Discussion

Most lifespan associated loci are linked with life shortening diseases

For example, some genes increased the chance Alzheimer's while others increased the chances of cardiovascular-related deaths. One locus was linked to smoking behavior.

The APOE gene increased survival rate during mid-life, and yet increased the chances of death in later life.

However, 3 loci had no known disease associations. Namely the genes WAPL, SRRM3, and IP6K1 are associated with longevity but not with life-shortening diseases.

WAPL was only found to be significant in the narrower birth cohort. Analyzing the same data in a different way, they used a wider birth cohort to increase statistical power. The downside to doing this was increased uncertainty in terms of censorship of long lived individuals. Censorship of long lived individuals means that the individuals could have lived longer than is recorded.

Below you see the effect on lifespan based on the cohort data used, where the horizontal lines represent the range of uncertainty. The effect of the WAPL gene, while not related to any known disease, appears to be, on average, detrimental to lifespan. However, the effect is less than one year of life, or many years of life for some of those with the allele?

Heterogeneity of GWA results across analyses

The increased number of persons from combining the two databases, led to a few different conclusions than previous studies on the individual databases. It could be that the sample sizes of the individual databases appear to be insufficient. In other words, the statistical power of the initial conclusions were too low. Or maybe certain genes could only possibly be of benefit in a British environment.

Another factor that could have led to the different results, is that the UK study used both the attained age of the living and the lifespan of deceased parents, while the AncestryDNA study only had access to full parental lifespans.

Missing heritability

The odds of inheriting a disease or lifespan or any phenotype can be surveyed on a population and is often labeled as h2. If the results of a GWA (genome wide analysis) finds all the loci that correlate to the specific phenotype, then these results should give the same odds of inheritance, where h2 = hg2.

However, with the research conducted over the last couple of decades, it has been found that phenotypes often have a complex association with numerous different loci, and the research does not find them all.

When research finds loci associated with a phenotype, the odds of the heritability of these loci is less than the odds of inheriting the phenotype. The issue of “missing heritability” is the failure of research to find all the genetic factors for heritability (hg2 is less than h2).

Studies have estimated lifespan h2 to be between 15-30%, while h2g is less than 10% as deduced from the heritability of the lifespan loci found in this analysis.

The authors explain in this and a past study that the discrepancy is not a failure to find the genetic components of lifespan, but instead the sociological phenomenon of assortative mating. Assortative mating is where individuals of similar phenotype or within the same culture mate with each other more frequently than would be expected from random mating. Even with their efforts to include assortative mating into the statistical analysis, they state that: “It is worth considering that the inflation of h2 estimates due to assortative mating may be more generally responsible for the recurrence of sizable “missing heritability” gaps.”

The significance of this conclusion, and of the GWA studies for lifespan phenotypes, is that there are no individual alleles that produce a long lived individual, only alleles that reduce lifespan.

— Marcos Reyes 2019/10/27 03:39